If you’ve been to any of my classes or workshops you’ll know that I absolutely love learning about anatomy, alignment, biomechanics and how it all relates to the practice of yoga. Over the years my understanding of the purpose of alignment in yoga or any movement practice has changed. Significantly.

I recently taught a workshop on this topic as part of a 200-hr. Yoga Teacher Training program and was inspired to share some insights here.

When I first started taking alignment in yoga seriously my understanding was that the purpose of paying attention to alignment was to get out of pain, prevent injury, to move and do yoga postures in a “correct and safe” way. In fact, several senior yoga teachers I studied with stated outright that there were correct or safe alignments and unsafe ones that would lead to pain or injury. Later I studied an alignment system developed by a biomechanist from outside the world of yoga that used 25 objective body markers (points) to assess an individual’s anatomical alignment. Still, throughout this 2-year program I thought the purpose was for safety, to move better and more correctly, and to prevent injury.

Let me give you a couple of common yoga alignment examples that you’ve probably heard:

“Don’t let your knee go past your ankle.”

“In Tree posture, make sure you place the foot above or below the knee but not directly on it.”

So what makes letting your knee go past your ankle inherently unsafe? Have you looked at your knees going up and down stairs? Your knees go past your ankle!! So why can’t we allow that in yoga?

Let’s take a look at what causes (human biological) tissue injury in the first place. Generally, an injury happens when the load (stress) applied to that part of the body exceeds its capacity to resist that load.

And how do we increase the capacity of a particular part of the body to withstand load? By loading it. Progressively. (Progressively loading suggests that over time we increase the amount of load applied).

If we never allow the knee to go past the ankle in our yoga or movement practice, perhaps out of fear for it being unsafe, we are intentionally not practicing loading the knee at that joint angle. When our knee finds itself in that position during normal everyday activities (maybe even while carrying something heavy) it is possible that we will overload the tissue (that had a history of not being loaded) and find pain or injury. Does this mean that knee past the ankle is a bad position? Or does it mean that not training the knee in that position left us with a decreased capacity for movement in our daily life?

When you start to look at the body in this way you realize how resilient the body is. “Overuse” injuries start to become “underloading” ones. Do you see the difference in messaging here? “Overuse” implies the body has a finite capacity for use, that as you get older you’re inevitably going to feel sore as things break down. It’s a pretty negative and movement-fearing view of the human body. On the other hand, taking a “movement optimist” (credit to Greg Lehman for coining that term) approach we would say “My body is resilient. It has an incredible ability to adapt to the movement inputs (and loads) I give it. I can load it in various ways to prevent injury. AND, if I end up with an injury I can use it as a learning opportunity – I guess I didn’t load that part of the body enough and when I feel better that’s exactly what I’ll start doing.”

So let’s agree to drop the idea that alignment in yoga is about safety or pain and injury prevention and remember instead that preventing pain and injury has more to do with progressively loading at a pace that allows our body tissues to adapt.

I want to note here that yoga is a very low-load activity. In general we are working with body weight only. Alignment may be more important during higher-load activities like lifting heavy for example. But remember injury risk is load-dependent and based on the tissue of the individual and its capacity to withstand load. And as mentioned earlier we know that tissues improve their capacity to withstand load by progressively loading. So maybe even with higher load some people can relax the alignment rules if they understand load and are applying it progressively to adapt their body and build capacity. Check out this guy to see what I mean:

View this post on Instagram

Single leg step downs _ Because I needed to make a new video for IG 💁🏻♂️🧔🏻 _ #BeardTheBestYouCanBe

So then is alignment ever important in our yoga and movement practices or should we forget about it altogether?

Think of alignment as being more about creating mindful intention. If I’m just trying to create a shape or yoga pose with my body and I’m not being particularly mindful about it, my body will generally choose the path of least resistance. In other words, whatever movements my body is most familiar and comfortable with it will use to get me to the general shape I’m interested in. But if I’m trying to target a specific area of the body – to stretch, strengthen or find greater mobility – I will want to be mindful of how I’m orienting my body and alignment markers help me see what parts are moving and what parts are not. The parts that are not moving well I like to refer to as “movement blindspots.” Paying attention to alignment helps me to see where my movement blindspots are. AND if my goal for my movement practice is to challenge my body, and to increase my available movement options, I might also want to direct the movement and loads to areas of the body that are not used to receiving them.

Increasing available movement options is a great way to gain resilience. I’m not going to get too much into the science of pain in this post other than to say that when certain movements aggravate our pain, we may want to avoid those movements for a while. We can use alignment to help us find an alternate pathway that isn’t painful.

There aren’t really good and bad, right and wrong ways to move. Ultimately, we want to be able to move in all the ways. Alignment is more about our intention with our practice in that moment. Increasing movement diversity and movement options are positive goals to increase resilience. If you’re competent in one way of doing a movement, why not challenge yourself in doing it a different way or for a different intention? You don’t have to do the same movement or yoga pose the same way everytime.

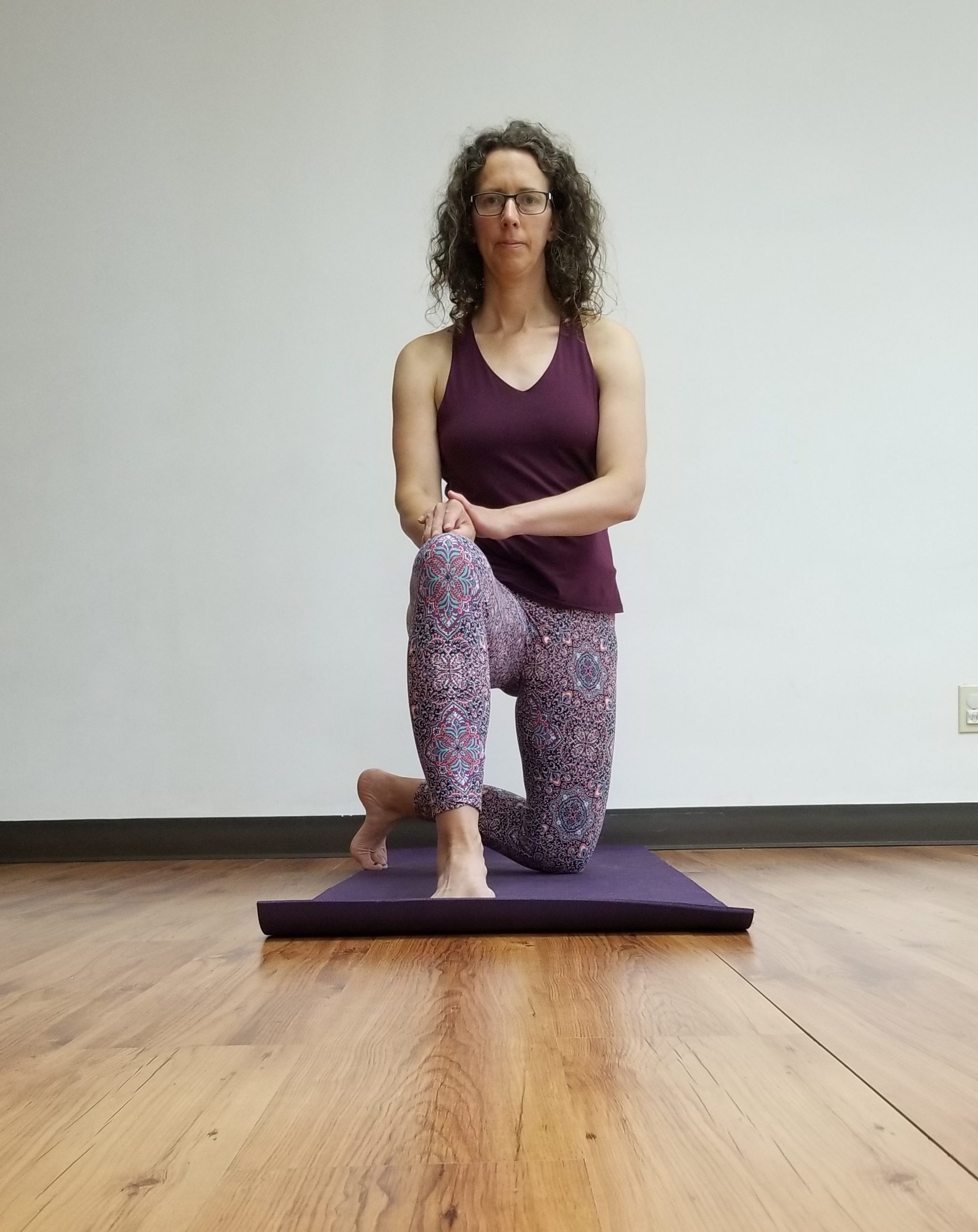

For example, back to the lunge. Here are a few photos demonstrating different alignments for a few different intentions.

Leaning way forward and testing my ankle dorsiflexion.

Hands down and working on untucking my pelvis and lengthening my front leg’s hamstring in this position.

Staying upright and tucking my pelvis to focus on stretching the hip flexors of the back leg and assess that hip’s extension ability.

Same version as above but now externally rotating the back hip to target different fibers of the hip flexors.

High lunge and leaning the knee in to intentionally load it differently – adducting and maybe even internally rotating the hip.

Doing the opposite and taking the knee out.

There are about 101 other ways I can use various lunge positions for different but specific intentions. And we haven’t even addressed adding external load. Do you see what I mean?

So alignment is still useful. But it is generally not about preventing pain and injury.

I want to thank Jules Mitchell, biomechanist and yoga teacher extraordinaire, for helping me change my perspectives regarding alignment.

If you have a comment on this blog, contact me to share your thoughts. If you are interested in an approach to yoga that emphasizes loading and challenging your movement blindspots to increase movement options, check out the RePose Fall Yoga Program. 10% off registrations before Aug 30